Handle Very Specific Strings Differently

In the past I was glad to see very specific strings in samples and sometimes used these strings as the only indicator for detection. E.g. whenever I’ve found a certain typo in the PE header fields like “Micorsoft Corportation” I cheered and thought that this would make a great signature. But – and I have to admit that now – this only makes a nice signature. Great signatures require not only to match on a certain sample in the most condensed way but aims to match on similar samples created by the same author or group.

Look at the following rule:

rule Enfal_Malware_Backdoor {

meta:

description = "Generic Rule to detect the Enfal Malware"

author = "Florian Roth"

date = "2015/02/10"

super_rule = 1

hash0 = "6d484daba3927fc0744b1bbd7981a56ebef95790"

hash1 = "d4071272cc1bf944e3867db299b3f5dce126f82b"

hash2 = "6c7c8b804cc76e2c208c6e3b6453cb134d01fa41"

score = 60

strings:

$x1 = "Micorsoft Corportation" fullword wide

$x2 = "IM Monnitor Service" fullword wide

$a1 = "imemonsvc.dll" fullword wide

$a2 = "iphlpsvc.tmp" fullword

$a3 = "{53A4988C-F91F-4054-9076-220AC5EC03F3}" fullword

$s1 = "urlmon" fullword

$s2 = "Registered trademarks and service marks are the property of their" wide

$s3 = "XpsUnregisterServer" fullword

$s4 = "XpsRegisterServer" fullword

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5A4D and

(

( 1 of ($x*) ) or

( 2 of ($a*) and all of ($s*) )

)

}

What I do when I review the 20 strings that are generated by yarGen is that I try to categorize the extracted strings in 3 different groups:

- Very specific strings (one of them is sufficient for successful detection, e.g. IP addresses, payload URLs, PDB paths, user profile directories)

- Specific strings (strings that look good but may appear in goodware as well, e.g. “wwwlib.dll”)

- Other strings (even strings that appear in goodware; without random code from compressed or encrypted data; e.g. “ModuleStart”)

Then I create a condition that defines:

- A Certain Magic Header (remove it in case of ASCII text like scripts or webshells)

- 1 of the very specific strings OR

- some of the specific strings combined with many (but not all) of the common strings

Here is another example that does only have very specific strings (x) and common strings (s):

rule Cobra_Trojan_Stage1 {

meta:

description = "Cobra Trojan - Stage 1"

author = "Florian Roth"

reference = "https://blog.gdatasoftware.com/blog/article/analysis-of-project-cobra.html"

date = "2015/02/18"

hash = "a28164de29e51f154be12d163ce5818fceb69233"

strings:

$x1 = "KmSvc.DLL" fullword wide

$x2 = "SVCHostServiceDll_W2K3.dll" fullword ascii

$s1 = "Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved." fullword wide

$s2 = "srservice" fullword wide

$s3 = "Key Management Service" fullword wide

$s4 = "msimghlp.dll" fullword wide

$s5 = "_ServiceCtrlHandler@16" fullword ascii

$s6 = "ModuleStart" fullword ascii

$s7 = "ModuleStop" fullword ascii

$s8 = "5.2.3790.3959 (srv03.sp2.070216-1710)" fullword wide

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5A4D and filesize < 50000 and 1 of ($x*) and 6 of ($s*)

}

If you can’t create a rule that is sufficiently specific, I recommend the following methods to restrict the rule:

- Magic Header (use it as first element in condition – see performance guidelines, e.g. “uint16(0) == 0x5A4D”)

- File Size (malware that mimics valid system files, drivers or legitimate software often differs significantly in size; try to find the valid files online and set a size value in your rule, e.g. “filesize > 200KB and filesize < 600KB”)

- String Location (see the “Location is Everything” section)

- Exclude strings that occur in false positives (e.g. $fp1 = “McAfeeSig”)

Location is Everything

One of the most underestimated features of Yara is the possibility to define a range in which strings occur in order to match. I used this technique to create a rule that detect metasploit meterpreter payloads quite reliably even if it’s encoded/cloaked. How that?

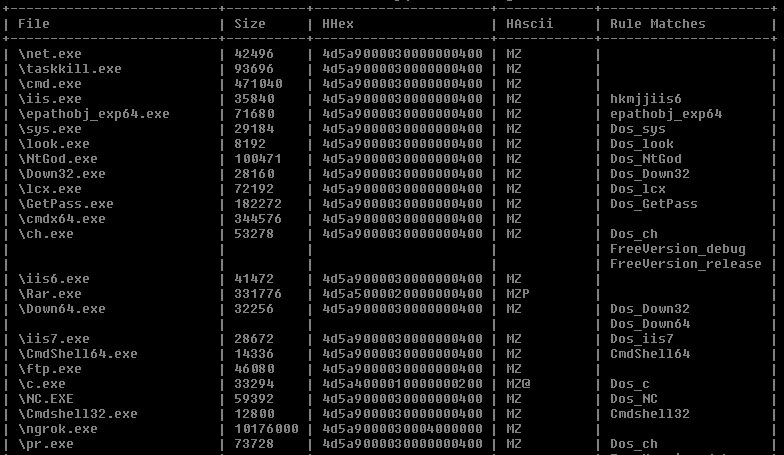

If you see malware code that is hidden in an overlay at the end of a valid executable (e.g. “ab.exe”) and you see only strings that are typical function exports or mimics a well-known executable ask the following questions:

- Is it normal that these strings are located at this location in the file?

- Is it normal that these strings occur more than once in that file?

- Is the distance between two strings somehow specific?

Malware Strings

In case of the unspecific malware code in the PE overlay, try to define a rule that looks for a certain file size (e.g. filesize > 800KB) and the malware strings relative to the end of the file (e.g. $s1 in (filesize-500..filesize)).

The following example shows a unspecified webshell that contains strings that may be modified by an attacker in future versions when applied in a victim’s network. Try always to extract strings that are less likely to be changed.

Webshell Code PHP

The variable name “$code” is more likely to change than the function combination “@eval(gzinflate(base64_decode(” at the end of the file. It is possible that valid php code contains “eval(gzinflate(base64_decode(” somewhere in the code but it is less likely that it occurs in the last 50 bytes of the file.

I therefore wrote the following rule:

rule Webshell_b374k_related_1 {

meta:

description = "Detects b374k related webshell"

author = "Florian Roth"

reference = "https://goo.gl/ZuzV2S"

score = 65

hash = "d5696b32d32177cf70eaaa5a28d1c5823526d87e20d3c62b747517c6d41656f7"

date = "2015-10-17"

strings:

$m1 = "<!--?php"

$s1 = "@eval(gzinflate(base64_decode(" ascii

condition:

$m1 at 0 and $s1 in (filesize-50..filesize) and filesize < 20KB

}

Performance Guidelines

I collected many ideas by Wesley Shields and Victor M. Alvarez and composed a gist called “Yara Performance Guidelines”. This guide shows you how to write Yara rules that use less CPU cycles by avoiding CPU intensive checks or using new condition checking shortcuts introduced in Yara version 3.4.

Yara Performance Guidelines

PE Module

People sometimes ask why I don’t use the PE module. The reason is simple: I avoid using modules that are rather new and would like to see it thoroughly tested prior using it in my scanners running in productive environments. It is a great module and a lot of effort went into it. I would always recommend using the PE module in lab environments or sandboxes. In scanners that walk huge directory trees a minor memory leak in one of the modules could lead to severe memory shortages. I’ll give it another year to prove its stability and then start using it in my rules.

yarGen

yarGen has an opcode feature since the last minor version. It is active by default but only useful in cases in which not enough strings could be extracted.

I currently use the following parameters to create my rules:

python yarGen.py --noop -z 0 -a "Florian Roth" -r "http://link-to-sample" /mal/malware

The problem with the opcode feature is that it requires about 2,5 GB more main memory during rule creation. I’ll change it to an optional parameter in the next version.

yarAnalyzer

yarAnalyzer is a rather new tool that focuses on rule coverage. After creating a bigger rule set or a generic rule that should match on several samples you’d like to check the coverage of your rules in order to detect overlapping rules (which is often OK).

yarAnalyzer helps you to get an overview on:

- rules that match on more than one sample

- samples that show hits from more than one rule

- rules without hits

- samples without hits

yarAnalayzer Screenshot

String Extraction and Colorization

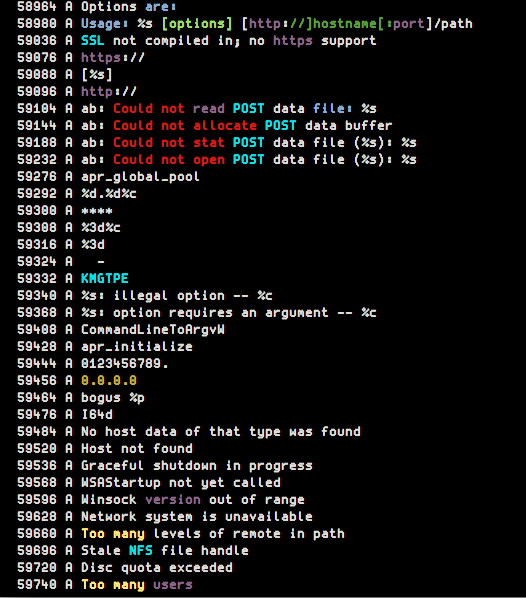

To review the strings in a sample I use a simple shell one-liner that a good friend sent me once.

“strings” version for Linux

#!/bin/bash (strings -a -td "$@" | sed 's/^\(\s*[0-9][0-9]*\) \(.*\)$/\1 A \2/' ; strings -a -td -el "$@" | sed 's/^\(\s*[0-9][0-9]*\) \(.*\)$/\1 W \2/') | sort -n

“gstrings” version for OS X (sudo port install binutils)

#!/bin/bash (gstrings -a -td "$@" | gsed 's/^\(\s*[0-9][0-9]*\) \(.*\)$/\1 A \2/' ; gstrings -a -td -el "$@" | gsed 's/^\(\s*[0-9][0-9]*\) \(.*\)$/\1 W \2/') | sort -n

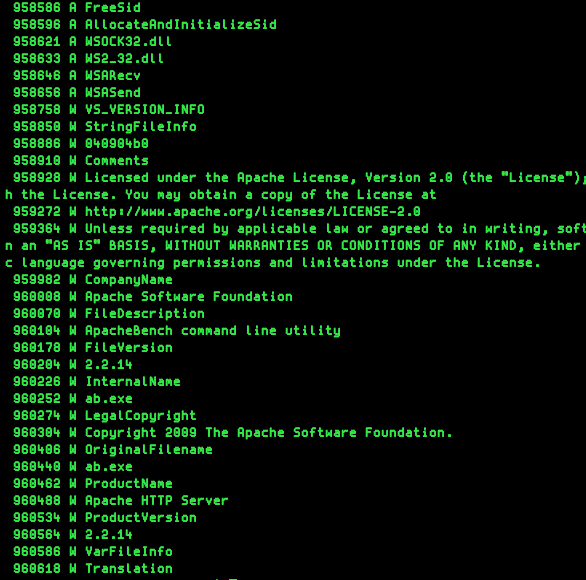

It produces an output as shown in the above screenshot with green text and the description “Malware Strings” showing the offset, ascii (A) or wide (W) and the string at this offset.

For a colorization of the string check my new tool “prisma” that colorizes random type standard output.

Prisma STDOUT colorization

Contact

Follow me on Twitter: @Cyb3rOps